The painting is monumental, taking up about a six by ten foot space on the museum wall; a space that now dances and swirls with brilliant color and untraceable abstraction. Straight and curved lines along with varied shapes of vivid color mingle on the canvas to create a haphazard, almost theatrical, experience. Taking in the piece, your eyes dart from side to side, top to bottom, trying to make sense of the colliding figures and colors. Finally you discover a central form, an oval, which seems to act as the eye of a compositional hurricane, surrounded by swirling color and form.

The piece is “Composition VII;” its creator, Wassily Kandinsky. It hangs on the bright white walls of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1995 along with only fourteen other Kandinsky paintings, together making up the exhibition “Kandinsky: Compositions.” In front of the painting stands an awestruck Aleta Pippin, attempting to memorize the active bursts of color that seem to radiate Kandinsky’s energy.

“Though only fifteen paintings were displayed, I was thrilled that we went to see the show,” said Pippin. “Pictures of art never do justice to the real thing. Seeing Kandinsky’s paintings in person was inspiring to say the least.”

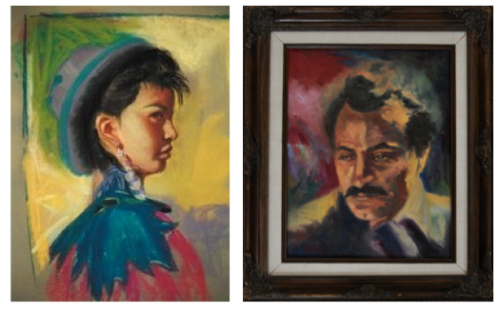

Pippin had begun painting just a few years earlier in 1992, and like Kandinsky, she started out creating representational work. Her paintings mostly consisted of portraiture, although the desire for abstraction seeped through in the blurring color that occupied the backdrops of her paintings.

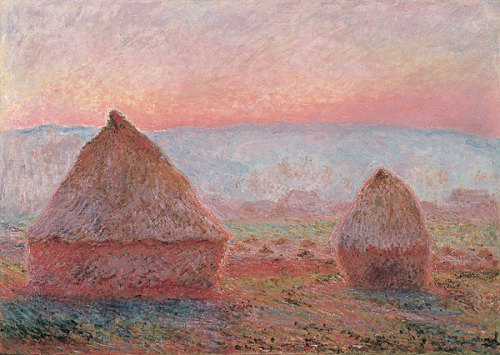

For Kandinsky, the transition into abstraction came in the early 1900s through a series of sparked inspirations, one of which was an 1896 Claude Monet exhibit in Moscow. He was astounded by “Haystacks at Giverny,” a series of Monet’s paintings depicting impressionistic haystacks in fields near Monet’s home in Giverny, France. Kandinsky later writes about his reaction to the work:

“It was from the catalog I learned this was a haystack. I was upset I had not recognized it. Dimly I was aware too that the object did not appear in the picture. And I noticed with surprise and confusion that the picture not only gripped me, but impressed itself ineradicably on my memory. Painting took on a fairy-tale power and splendor.”

Another push towards abstraction for the Russian artist, who is credited as being the first purely abstract painter, came from looking at his own work in a different light. One night when Kandinsky came home to his studio, he was enchanted by a painting he did not recognize. After a closer look, he realized it was his own piece lying on its side. Kandinsky recognized that subject matter lessened the impact of his paintings, and from that point on he began removing it from his work. This would eventually earn him the title of “the father of abstraction,” and “pioneer” of the Abstract Expressionist movement.

For Aleta Pippin, the move toward abstraction resulted from a desire to experiment with imagery, color, and various media. She relates to Kandinsky’s epiphany of removing the subject matter for a more timeless and freeing composition.

“When someone views a painting containing subject matter, there is a reaction based on their relationship to that subject,” explains Pippin. “If they’re viewing an abstract painting, they have the opportunity to consider it on a deeper level, for instance, simply enjoying the color or perhaps analyzing the artist’s message.”

Kandinsky, also a renowned art theorist, took a spiritual approach to his work, analyzing the effects of color on the mind and soul. In his book, “Concerning the Spiritual in Art,” he explored his theory that color can create an “inner resonance” with the viewer by provoking a sensory experience within their soul.

Left: “Riding the Range,” Aleta Pippin, acrylic/canvas, 36×36.” Right: “Improvisation 26,” Wassily Kandinsky, oil/canvas, 1912.

To say Kandinsky was a “colorist” is an understatement; he devoted his life to it, which is why Pippin couldn’t look away as she stood before his paintings in LACMA on that June afternoon in 1995. Her work thrives on color and has a similar spiritual bent. “I believe that true art comes from within; color is central to my individual expression,” says Pippin.

The trickling effect of artists inspiring artists is how art movements are born, with creative leaders carrying the influence of master artists that came before them. For Pippin, inspiration comes from artists living and dead who appreciate a sense of color along with timeless and spiritual interpretations of abstract ideas. The visual expressions of Gerard Richter and Claude Monet have directly influenced Pippin’s paintings, and abstract expressionists like Kandinsky, Rothko, and de Kooning serve as an overall inspiration to her painting style.

With these artists as her guides, Pippin creates liberating works of art with an intuitive use of color and energetic freedom. See her vibrant abstractions hanging at Pippin Contemporary for your own interpretive experience, or find them on her artist page of our website.